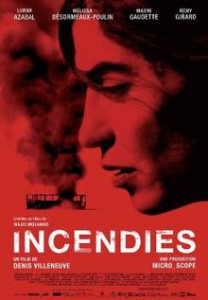

Sunday January 4th 2015, Movie Night: Incendies (Scorched) by Denis Villeneuve (130 minutes, 2010). In Arabic and French, with English subtitles. Door opens at 8pm, film begins at 9pm.

Sunday January 4th 2015, Movie Night: Incendies (Scorched) by Denis Villeneuve (130 minutes, 2010). In Arabic and French, with English subtitles. Door opens at 8pm, film begins at 9pm.

People who have lived through noteworthy experiences – fascinating or tragic – have always inspired writers and filmmakers. Soha Bechara is one such figure. A militant with the communist resistance to the Israeli occupation of south Lebanon, Bechara was imprisoned without trial when she was 21 for trying to assassinate Antoine Lahad, the leader of the Israel-backed South Lebanon Army. She spent 10 years in Khiam prison, six of them in solitary confinement.

Bechara’s story has captured the imagination of Lebanese filmmakers and since her release from Khiam in 1998, she has appeared in a number of documentary studies. Now, in the wake of these artful documentaries, the first of the fiction films has come: “Incendies”. Villeneuve’s film is based on the play of the same name by Lebanese-Canadian playwright Wajdi Mouawad. The plot of “Incendies” revolves around the character of political activist Nawal Marwan, who lived through a harrowing detention before leaving her fictional home country for a life of exile in Canada. Her story is loosely inspired by Bechara’s own experiences.

Villeneuve was in Geneva for the premier in January 2010. Bechara, who moved to Geneva via Paris following her release from Khiam, was also present and the film director told the audience that this screening was particularly important because the inspiration for the film was in the room.

Bechara hails from the Christian village of Deir Mimas in southern Lebanon, which came under frequent Israeli attacks in the 1970s before its occupation in 1982. Bechara has always maintained that her actions were against the Israeli occupation, an element that is missing from Villeneuve’s film.

“Incendies” was filmed in Jordan and uses actors with a variety of Arabic accents – from Syrian and Jordanian to Moroccan. Villeneuve tried to keep things abstract, says Bechara, “but he used symbols like refugee camps, crosses, headscarves and a bus massacre [a reference to the Ain al-Remmaneh massacre, which is conventionally said to be the incident that started the civil war], which made it so that it could only be Lebanon. It’s as if he was pointing his finger at us.”

Wajdi Mouawad met Bechara in Paris just after her release from Khiam at the home of the late Lebanese filmmaker Randa Chahal. Chahal had made a documentary about Bechara, “Souha: Surviving Hell,” and filmed Bechara’s return to Lebanon as she revisited the Khiam detention center once Israel had fled the country in the spring of 2000.

“Wajdi was already working on a play,” Bechara recalled. “He had seen Randa’s film, had read my book [“Resistance: My Life for Lebanon”] and all these ideas were a point of departure. He built his story little by little and the play became abstract – the soul of his play was the fact that it was abstract. This was its strength.

“I think the director [Villeneuve] tried to remain faithful to Wajdi and to the text,” Bechara continued. “He tried to put himself in Wajdi’s shoes and didn’t quite manage. Wajdi had made a play that was universal, whereas [Villeneuve] brought it closer to Lebanon with all its cliches. I’m not even sure why it had to be in Arabic.”

When it comes to the Lebanese Civil War, Bechara said, Westerners tend to fall prey to cliches. “The war wasn’t between Christians and Muslims. You can’t just simplify things. Christians killed Christians and Muslims killed Muslims. And the foreign element wasn’t there, which is a problem when it comes to the prison scenes.”

In Lebanese militia prisons there were no women, Bechara explained. Israelis and Syrians ran the only two prisons in which women were held.

To be fair to Villeneuve, anyone unfamiliar with the region or the history of Lebanon’s Civil War won’t notice whether details are particular to Lebanon, or miss the presence of the occupying force that was so integral to the history at the core of the story.

What they will leave the cinema with is the feeling of having exercised a range of emotions: hate, rage, redemption and love.

When she watched a scene where “her” character, the imprisoned Marwan, tries not to hear the cries of prisoners being tortured, Bechara said she did feel transported back to Khiam. “In a flash, it brings you back to that world,” she says. “Anyone who has experienced this will relive it for a second.”

After Khiam prison was destroyed by the Israeli air force in 2006, Bechara returned to visit what was left. “I felt lost,” she recalled. “I couldn’t find my bearings anymore. It was in ruins. The torture cells are still there as well as prison number one, the guards’ section and the isolation cells for men. But the two women’s sections are a heap of rubble.

“But you can’t erase the memory of a place,” she said. “It goes beyond Lebanon. It’s the history of humanity.”

Dar al-Saqi recently published a book Bechara co-authored with Cosette Ibrahim, who was also imprisoned in Khiam, entitled “I Dream of a Prison made of Cherries.”

“This book was very important for me and with the destruction of Khiam it became inevitable,” Bechara said. “I worked on it for four years, collaborating with lots of people. It became another form of resistance.”

Unlike the fictional character that is based upon her – whose grown children have no idea about their mother’s former life – Bechara says her two daughters do know about her past. Khiam, she remarks, is part of her life although it doesn’t burden her daily existence.

She has objects in her home that were made in Khiam, and her eldest daughter knows that she was in prison as a resistance fighter. She explains to her the similarities of her situation to a local festival in Geneva, when the Swiss celebrate the defeat of troops sent by the Duke of Savoy in the 17th century.

Besides her work for the advocacy group Collective Urgence Palestine, Bechara is sometimes asked to speak to Amnesty International or the Red Cross about torture and confinement. “It’s a subject that I know so well,” she said, “but I can speak about it with great distance.”

There may be little of her life in Mouawad and Villeneuve’s fiction, but that doesn’t mean she doesn’t find the fiction compelling. Bechara says that she had seen the theater production four times. She sat through the film too, and enjoyed it, which, she says, is rare.

Film night at Joe’s Garage, cozy cinema! Doors open at 8pm, film begins at 9pm, free entrance. You want to play a movie, let us know: joe [at] squat [dot] net